“Everyone may know of your idea; even though, it will never be as it real as you thought.” ― Alan Maiccon

Independent filmmaking is often a dubious and quixotic endeavor, better-suited for chess players than first-person shooters. Truly, a get-poor-quick scheme that only promises seemingly endless pitfalls and compromises. Producing a finished piece requires a manic tenacity and a visceral connection to the concept of delayed gratification. It involves the planting of many seeds with the knowledge that it may take months or years to see anything come to fruition.

Clint Bentley, a 34-year-old Dallas-based filmmaker, understands this.

Having grown up on a working cattle ranch near Daytona Beach, Florida, Bentley was often alone with his thoughts and his chores. Performing difficult work that might not show results for extended periods of time. This arduous environment developed a work ethic and mindset that has become a valuable asset to his current career.

The Bentley family back then didn’t have cable, so rented movies were the main form of entertainment in their doublewide. There were no friends nearby, so free time was often spent alone in wooded areas that were peppered with old and weathered abandoned structures. Plenty of fodder for a young person’s imagination.

An English major in college, Bentley took a hiatus from his studies to try his hand as a singer-songwriter, living in friend’s stairwell in New York. It proved to be a short-lived digression — Bentley quickly realized that particular brass ring was safely out of his reach. His time in NYC wasn’t entirely a bust — while there, he was exposed to foreign films that inspired him and expanded his worldview.

Bentley returned to Stetson University with this new appreciation for film to finish his Literature degree. He wanted to make a documentary about the U.S. – Mexico border and applied for and received a SURE grant from the school to finance it. As the grant was $2500, it basically paid for a modest camera, some travel expenses and little else. It was titled, “Boulders Fall to Each.”

After college, Bentley took a stab at making some short films, one was titled “I’ll Remember Everything”, which he describes as a “pretentious film with a pretentious title.” But these early forays provided some personal and professional calibration. “What kind of stuff gets you off, and what kind of stuff do you not care about? There’s only one way to find that out, and that’s by doing it. Everybody’s a perfect filmmaker when they are sitting around dissecting other people’s movies,” said Bentley.

In 2010, Bentley’s parents decided to move to Texas. Bentley himself was toying with relocating to Austin or Paris when he met his now-wife Rachel. She introduced him to a guy named Greg Kwedar that she went to college with at Texas A&M. Kwedar was a filmmaker who had been doing some things at the border as well.

Bentley and Kwedar hit it off and began collaborating on a feature-length film about the Border Patrol called “Transpecos”. It would only take them six years to get it made.

The script for “Transpecos” went through several phases over the years, with the final shooting version being a good deal more conservative in scope versus one of the earlier drafts, due to time and financial constraints.

While fundraising for “Transpecos”, Bentley and Kwedar decided to make a short film called “Dakota” — a similarly-themed proof of concept. Making “Dakota” allowed them to get a better feel for the logistical hurdles to come and provided a test drive for their new roles: Kwedar as director and Bentley as producer.

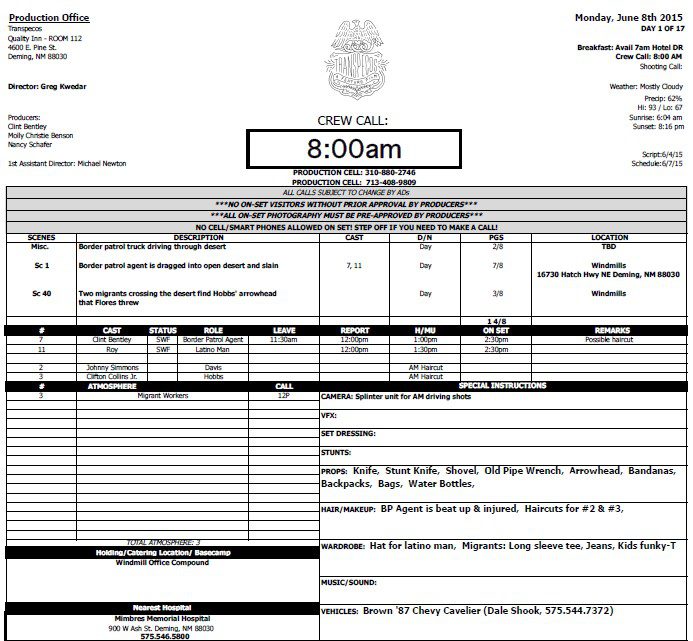

Production on “Transpecos” finally began on June 8, 2015. A mere 17 days were allocated to shoot the entire film, most of which was set in a sweltering desert area outside of Deming, New Mexico. The average temperature was 112 degrees. Some crew member’s shoes were melting on the pavement during production.

“Transpecos” wound up being a hit on the 2016 festival circuit, including the prestigious South by Southwest Film Festival, where it won the audience award for best narrative feature. It was then picked up for distribution by Samuel Goldwyn Films. Bentley and Kwedar were chosen among the 25 screenwriters to watch in 2017 by MovieMaker Magazine. Bentley was all set.

Then his alarm clock went off.

“I thought it would be more successful than it was. I thought it would be easier. It took about four years to raise the money. After it was done and had turned out decent, I thought, alright, all our dreams are going to come true. I told my wife that when we sold it (‘Transpecos’), I was going to buy a motorcycle. I didn’t realize selling the movie doesn’t make you any money. I got back from shooting ‘Transpecos’ and was having to take little odd production jobs.”

“‘Transpecos’ did well for itself, made more than was spent on it. However, the distributors skim so much off the top of each online play. This starts even before the investors are repaid. There was a lump sum that was initially paid out, but it’s not a very big lump. The rest of the film’s income is directly tied to sales.”

Bentley and Kwedar have now been working together for almost a decade, they are currently juggling 6-7 projects in different stages of development. While they don’t have a written down, exclusive agreement (Bentley does some freelance writing on the side and Kwedar has helped produce a couple of documentaries), the vast majority of their efforts are collaborative.

“The best part of having a partner is that you have someone to celebrate with when things are good, and someone to commiserate with when no one is calling, and things are shitty. I realized how rare that is in the filmmaking world to have somebody else in the trenches with you all the time. It’s also hard to find someone who will be honest with you about your work, and you as a person.”

Years can go by while each endeavor is finding a home. Two of their projects are both over three years old at this point. There can be some epic, faith-testing lulls to navigate. “These days, I always try to keep working, even if nothing is happening or coming through.”

One such lull drove Bentley and Kwedar to put one of their older projects on the front burner. A narrative feature film about an aging horse jockey who is facing his last season. “We just figured out what the bare minimum amount we’d need to raise to get it made and drummed up the funding.”

They had already produced a jockey-themed short film in 2016 called “9 Races”, which, like “Dakota”, was a test run at the feature film’s subject matter. This time Bentley would direct and Kwedar would wear the producer hat.

“Jockey” examines the different aspects of professional horse racing — a routinely dangerous lifestyle where accidents are common, and jockeys often continue to work while injured. One of the initial inspirations for “Jockey” (the film’s current working title) was Bentley’s father, Robert Glenn Bentley — a horse trainer and rancher who had been a jockey himself for decades.

Years after having retired from racing horses, Bentley’s father was diagnosed with injury-related ALS and passed away on New Year’s Eve in 2014.

“Jockey” recently completed production, almost entirely at the Turf Paradise racetrack in Phoenix, Arizona. Bentley and Kwedar had largely chosen Turf Paradise over other U.S. tracks because of its old-school appearance and the wealth of interesting characters that inhabit the place.

The film is unique on a couple levels; they only hired three Screen Actors Guild actors and the rest of the cast is comprised of various denizens of the track, including the general manager and the head of security.

What also makes this project different is how the film is being financed. Along with utilizing traditional investors, the film’s crewmembers all agreed to work for below-market rates in exchange for being investors in the project. Typically, this is called a deferred payment, often cynically referred to as a “de-freed” payment — as very few such projects ever see any return at all. The difference this time is that the crew will see any incoming revenue at the same time the investors do, not after paying them back first.

This arrangement allowed for less money to be raised up front and made for a more collaborative on-set environment — as everyone has a personal stake in the outcome. “The beauty of it was that we could immerse ourselves in the community, the crew is allowed to make creative suggestions to improve the end product.”

As soon as production on “Jockey” had begun in earnest, one of the studios that Bentley and Kwedar had been in stalled talks with decided they wanted them to start writing a script for them. Work begets work. “This would be our first one to try within the big studio system. To try and make something with a point of view and says something, while also trying to appease a large company that is trying to appeal to the most people. It can feel like the tail is wagging the dog, but you just kind of give yourself up to it, this is what we’re doing, let’s see what happens.”

Bentley has acknowledged some previous misconceptions about the business. For one, he has sworn off attempting to predict how his colleagues’ projects would fare. “It’s funny, the movies that I thought did great didn’t do that well, then I’d find out some others I thought wouldn’t do as well are doing great.”

Bentley also used to tie financial success to personal success. “Before ‘Transpecos’, I was thinking, if it makes money that will be a success. If I make money off of it, that will be a success. I’ve not made a dime off of it (‘Transpecos’) compared to what I’ve spent to get it made out of pocket, but I feel great about it. It doesn’t change my feelings about that movie at all.”

Bentley recalls a moment where he accidentally received some commiseration from the cosmos. “Greg and I were in New York for some meetings, it was cold and late and there was an Italian restaurant that only had outside tables available — so we grabbed one. Another couple of guys did the same thing. One of them happened to be director Cary Fukunaga, who had been directing the series True Detective and had just completed the film, Beasts of No Nation. Fukunaga was saying to his friend, ‘Man, I just need to make some money, I just gotta figure out how to make some cash soon.’ Just hearing him gripe about the same things we had been griping about was very eye-opening. It was more encouraging than anything, knowing that this guy who I look up to is struggling as well.”

Bentley has this to offer up-and-comers, “If I can tell any young (independent) filmmaker anything, don’t expect this to be what you make money off of. You can make some cash in the commercial world.”

“I grew up poor. I’ve been broke at times, I’ve had money at times. Being broke doesn’t bother me. As long as my eyes are open going into it and have my expectations set, I’m fine with it.”

“Now that ‘Jockey’ is done I think I’m gonna try to pick up a couple commercials.”